Knowledge Base

The Importance of Room Acoustics

© 2016 Steve Feinstein, inMusic, Inc.

Nothing can make or break the sound of your performance, your rehearsal space, a recording venue or a home entertainment system more than room acoustics. You may have the very best instruments, speakers, amplifiers and recording equipment and you may have placed it all perfectly in your space, but if your performance/recording/listening room has poor acoustics, you’re really facing an uphill battle.

Luckily, there are a lot of things you can do to improve even the worst spaces. Remember that old cliché, “Moderation in all things”? Well, that applies to room acoustics too.

What you want to do is create a room that is neither too “live” nor too “dead.” A “live” room is a room with a preponderance of hard, reflective surfaces. Lot of exposed glass windows, hardwood floor, things like that. The room sounds like your high school gymnasium—things seem to echo forever. (See figure 1.) Those excessive echoes make it hard to distinguish between individual instruments and vocalists in the music. Everything smears together in a harsh cacophony of overly-bright, hard-edged sound. The original warm, organic sound is lost and you’re left with a shrill, indistinct, tinny caricature of what the music should sound like.

Figure 1—Overly “Live” Room

Here’s a very reliable test you can perform to see if your space is too live and reflective—and best of all, it doesn’t require any expensive test equipment or special expertise in acoustics or physics. It’s called the “slap echo” test and it works like this: Slap your hands together. Now listen for the after-effect, the “echo.” In a space with balanced acoustics, there will be some audible after-slap reverberation, but not too pronounced. Instead, it’ll sound like an “answer” to your handclap and it follows the handclap pretty quickly.

In an overly live space, the echo that follows the handclap will be fairly loud and quite distinct from the original clap itself. It’ll have a “twangy” quality that sounds very different than your original handclap. Overly live room acoustics will impart that twangy coloration to the original music, making it sound blurred and ill-defined.

The other extreme is an overly damped, “dead” space: thick-pile carpeting, heavy floor-to-ceiling draperies, and dense, over-stuffed furniture. A room like this sounds like you’re trapped in a small coat closet packed with winter coats. Totally muffled and closed in. (See figure 2.)

Figure 2—Overly “Dead” Room

In this kind of space, the slap echo test won’t produce any meaningful after clap “reverberation answer” at all. You’ll hear the sound of your handclap, right there in front of you, and pretty much nothing else.

Without going into all kinds of arcane detail about the nature of sound propagation in rooms, like delay times as measured in milliseconds, the inverse square law, absorption coefficient vs. frequency, etc., remember these essentials. There are two kinds of sound:

1. Direct sound, which is the sound that reaches your ears directly from the sound source itself. We use direct sound to gauge direction and general tonal quality.

2. Reflected (indirect) sound. This is the sound that bounces off the walls, floor and the ceiling before reaching your ears. We use this sound to gauge the distance we are from the sound source and the size of the environment we’re in.

The reflective/absorptive qualities of the room’s surfaces define the “live-dead” character of the sound. It’s the mix of those sounds that determines the overall listening/performing/recording quality of a given space. Recording venues have all kinds of special additional considerations, which are well beyond the scope of this modest article. Controlling the direct/reflected nature of individual instruments and singers is a specialized art onto itself and the general acoustics of the recording environment—while they still adhere to the basic goal of a good balance of absorptive/reflective surfaces—will be modified and optimized by the recording engineer depending on the specific challenges presented by the performer(s) and the specific goals of the recording.

For the rest of us, we should try to create an acoustic environment with a good balance of reflective and absorptive surfaces. Throw an area rug down on a hardwood floor or hang a tapestry on the wall to ameliorate overly live conditions. There are also lots of wall-hanging sound absorbers/diffusers available that are simple to install and help a great deal. (See figure 3.)

Figure 3—Wall-Mounted Sound Absorber

Sometimes there’s not too much you can do about a performance venue, especially in a large space that wasn’t intended for musical/spoken word productions. There are some good portable sound absorption panels that you can place around a small club or coffee house (depending on the owner’s consent and practical seating/safety considerations, of course!) to counteract the overly reflective nature of the interior brick walls commonly found in such spaces. (See figure 4.)

Figure 4—Portable Sound Absorption Panel

Here is a very informative 3-minute video about how sound works in rooms—direct and reflected sound. It’s well worth the time to watch it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JPYt10zrclQ

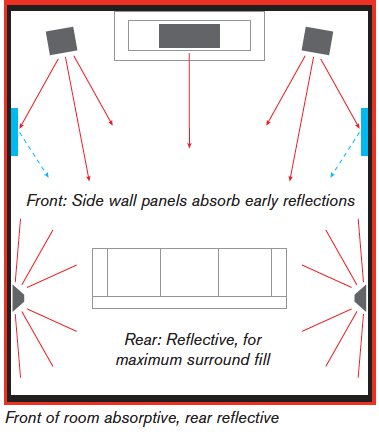

For domestic listening environments like a “surround sound” home theater, an excellent general strategy is what’s known as the “dead-end, live-end” approach. This method of shaping room acoustics says that you should try to “deaden” the front half of the listening room to minimize early reflections, thus enhancing the intelligibility of the direct sound—which is where the spoken dialog in a movie originates—from the Left-Center-Right speakers (often called the “front stage” speakers). One good way to do this is to place sound-deadening panels on the sidewalls to absorb the front speakers’ first reflections. (See figure 5.)

Figure 5—“Live End-Dead End” Home Theater Acoustics

Conversely, try to keep the rear of the home theater room relatively reflective, since you want the sound from the surround speakers to reflect around the rear of the room as much as possible to fill that area with ambient sound.

To sum up: Whether it’s a home music listening room, a small club performance venue or a basement recording studio over your friend’s house, you should always try to maintain a good balance of absorptive and reflective surfaces, as much as practical. If you can do that, you have a reasonably good chance of getting a good-sounding room, one that will work with you instead of against you.